Arabic Calligraphy

By Ma’n Abul Husn (Al Shindaga : July/August – 2006)

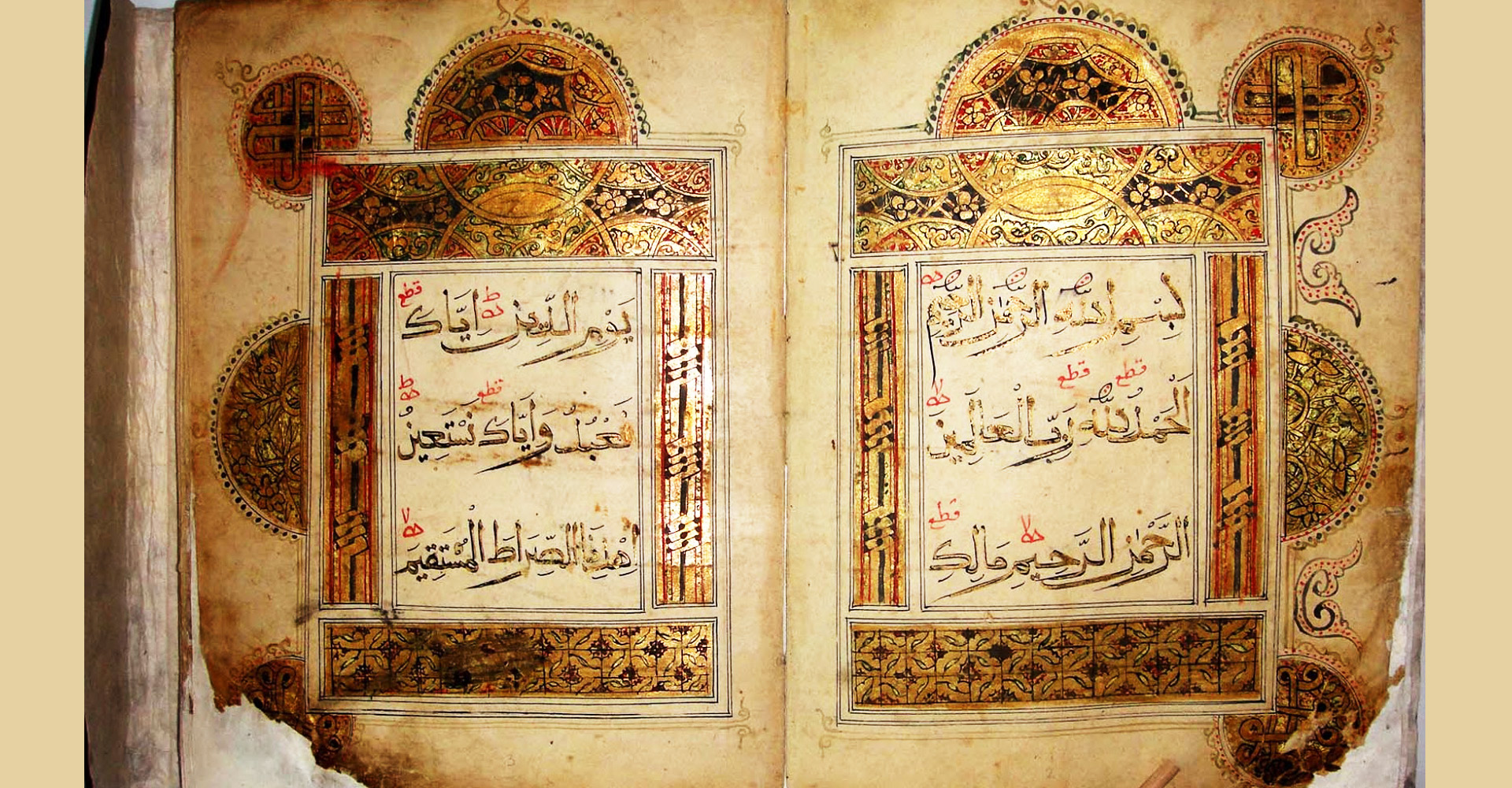

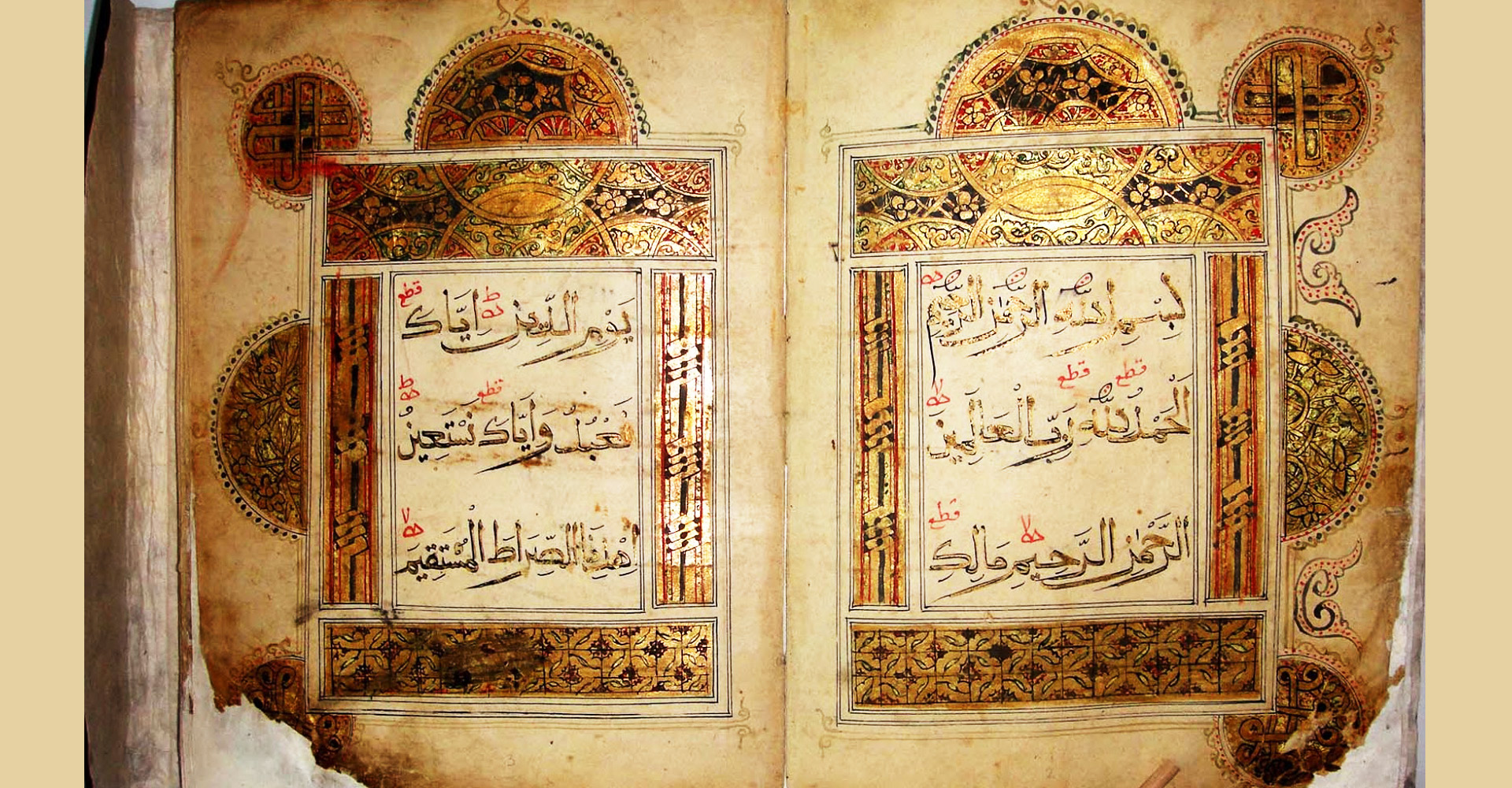

Arabic calligraphy is characterized by flowing patterns and intricate geometrical designs. This fine writing, which, Alexandrian philosopher Euclid called a “spiritual technique,” has poured forth from the pens of Arabs for the last thirteen centuries.

In a broad sense, Arabic writing is merely calligraphy, a tool for recording and communicating; but in the Arab world it is an art with remarkable history; a form with great masters and revered traditions. Beauty alone distinguishes calligraphy from ordinary handwriting. Writing may express ideas, but to the Arab it must also express the broader dimension of aesthetics.

Throughout the centuries, calligraphy remained a supreme art form, replacing design, painting and sculpture. Calligraphy was not only found in palaces and mosques, but on clothing, carpets, decorative items and literary works.

From the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem to the great mosques of Isfahan in Persia, calligraphy decorated, enhanced and even helped to visually unify the greatest Muslim structures.

The art of Arabic calligraphy was employed in many European churches as well; such as in Saint Peter’s Cathedral in Rome. The representations of Christian Saints that beautify the Capella Palatina in Palermo, Sicily, bear inscriptions in Kufi, the early arabic script.

Calligraphy is an aspect of Islamic art that has evolved alongside the religion of Islam and the Arabic language. While many religions have made use of figural images to convey their core convictions, Islam has instead used the shapes and sizes of words or letters.

Given Islam’s taboo against pictorial representation, drawings could not be used to illustrate the Qur’an, as was done in the Christian world. Calligraphy has arguably become the most venerated form of Islamic art because it provides a link between the languages of the Muslims with the religion of Islam.

Anthony Welch, Professor of Islamic Art and Architecture, writes that the primary reason for the chronological, social, and geographic persuasiveness of the calligraphic arts in the Islamic world is found in the Holy Qur’an.

Welch cites the following quote from the Qur’an:

“Thy Lord is the Most Bounteous,

Who teacheth by the pen,

Teacheth man that which he knew not.” (96:3-5)

Over centuries, Arabic lettering has achieved a high level of sophistication, and Arabic scripts can vary from flowing cursive styles like Naskh and Thuluth to the angular Kufi.

Arabic writing belongs to the family of Semitic alphabetical scripts in which mainly the consonants are represented. Arabic script was developed in a comparatively brief span of time to become a widely used alphabet. Today, it comes second in use only to the Roman alphabet.

The lives of the early Arabs were hard before Islam, but their culture was prolific in terms of writing and poetry. Long before Islam, Arabs acknowledged the power and beauty of words. Poetry, for example, was an essential part of daily life. The early Arabs felt an immense appreciation for the spoken word and later for its written form.

Arabic script is derived from the Aramaic Nabataean alphabet. The Arabic alphabet is a script of 28 letters and uses long but not short vowels. The letters are derived from only 17 distinct forms, distinguished one from another by a dot or dots placed above or below the letter. Short vowels are indicated by small diagonal strokes above or below letters.

Writes Welch: “Written from right to left, the Arabic script at its best can be a flowing continuum of ascending verticals, descending curves, and temperate horizontals, achieving a measured balance between static perfection of individual form and paced and rhythmic movement. There is great variability in form: words and letters can be compacted to a dense knot or drawn out to great length; they can be angular or curving; they can be small or large. The range of possibilities is almost infinite, and the scribes of Islam labored with passion to unfold the promise of the script.”

As Islam spread beyond the boundaries of the Arabian Peninsula, people around the world welcomed the new faith. The new Muslims interpreted the art of writing as an abstract expression of Islam, each according to their own cultural and aesthetic systems.

This cultural diversity led to the birth of regional calligraphic schools and styles such as Ta’leeq in Persia and Deewani in Turkey.

When the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) died in 632 CE, the Qur’anic revelation stopped. The content of the Holy Qur’an was passed from lip to lip. However, Omar Ibn Al Khattab, one of the disciples of the Prophet Muhammad, urged the Caliph Abu Bakr to put the Holy Qur’an in writing.

At the time only two scripts with distinctive features were maintained. They were Muqawwar, which was cursive and easy to write, and Mabsut which was elongated and straight-lined. These two scripts had their impact on the development and creation of new styles, the most important being Ma’il (slanting), a kind of primitive Kufic script; Mashq (extended); and Naskh (inscriptional).

The Ma’il script failed to achieve relative popularity and was replaced by the angular Kufic script. On the other hand, the Mashq and Naskh were used extensively after considerable technical improvements.

The development of Arabic calligraphy did not follow a chronological line. A number of various forms appeared simultaneously.

The intense and dramatic early development of writing ended with the rise of the Umayyad dynasty (661-755). According to Yasin Hamid Safadi in his Islamic Calligraphy (1978), the Umayyad caliph Abdul Malek Ibn Marwan (685-705) was the first to legislate the compulsory use of Arabic script for all official and state registers.

Damascus was the Umayyad capital and was an important political and cultural center. During the Umayyad era, two new Arabic scripts appeared, Tumar and Jali. These scripts were invented by the famous calligrapher Qutbah Al Moharir. Later, improved versions of the Tumar and Jali scripts were developed and then used during the Abbasid dynasty (750-1258).

Tumar was formulated and extensively used during the reign of Mu’awiyah Ibn Abi Sufyan (660-679), the founder of the Umayyad dynasty. Tumar became the royal script of the succeeding Umayyad caliphs.

Calligraphy entered a phase of glory under the influence of Abbasid vizier and calligrapher Ibn Muqlah (886-940). According to Welch, Ibn Muqlah is regarded as a figure of heroic stature who laid the basis for a great art upon firm principles and who created the Six Styles of writing: Kufi, Thuluth, Naskh, Riq’a, Deewani, and Ta’leeq.

Ibn Muqlah was followed by Ibn Al Bawwab in the 11th century and Yaqut Al Musta’simi in the late 13th century. The two great calligraphers built on Ibn Muqlah’s achievements. Each of the three men was viewed as an exemplar of certain admirable personal characteristics and as a model for necessary calligraphic skills.

The Abbasid dynasty came to an end in 1258 when Baghdad was sacked by Mongol armies. That was a major turning point in the history of Islamic culture, especially in the fields of arts and architecture. Abaqa (1265-1282), the son of Hulagu, established the Ilkhanid dynasty in Persia. Then, Hulagu’s great-grandson Ghazan (1295-1305) embraced Islam and made it the state religion.

Ghazan, taking the Muslim name of Mahmud, dedicated himself to the revival of Islamic culture, arts, and traditions. The impact of Ghazan’s reforms continued through the reigns of his two successors, his brother Uljaytu (1304-1316) and his nephew Abu Sa’id (1317-1335). During this era, the arts of the book industry and calligraphy were at their zenith.

Abdullah Ibn Muhammad Al Hamadani was commissioned by Uljaytu to copy and illuminate the Holy Qur’an in Rayhani script. Ahmad Al Sahrawardi, another master calligrapher and a student of Yaqut Al Musta’simi, copied the Qur’an in Muhaqqaq script. Many master calligraphers contributed significantly to the production of fine copies of the Qur’an in Rayhani and Thuluth scripts including Abdullah Al Sayrafi, Yehya Al Jamali Al Sufi, and Muhammad Ibn Yousuf Al Abari.

By the end of the 14th century, the Timurid dynasty had succeeded the Ilkhanids in Persia. The arts and architecture under the Timurids and their contemporaries set a standard of excellence and elegance for generations in Iran, Turkey, and India.

According to Safadi, the Timurid style aimed to create a balance between beauty and grandeur by combining clearly written scripts in large Qur’ans and extremely fine, intricate, softly colored illumination of floral patterns integrated with ornamental eastern Kufic script so fine as to be almost invisible. The calligraphers of this era were the first to use various styles with different sizes of scripts on the same page when copying the Holy Qur’an. Under Timurid patronage, the most impressive and largest copies ever of the Holy Qur’an were produced.

The Mamluks founded their dynasty (1260-1389) mainly in Egypt and Syria. During the Mamluk era, architecture was the pre-eminent art, and the Mamluks’ patronage defined many Islamic arts. Objects like lamps, glass, brass candlesticks, paper Qur’an manuscripts, and wooden minbars (mosque pulpit) were well designed, calligraphed, and decorated.

There were many master Mamluk calligraphers whose works exhibit superb artistic skills including Muhammad Ibn Abdul Wahid, Muhammad Ibn Sulayman Al Muhsini, Ahmad Ibn Muhammad Al Ansari, and Ibrahim Ibn Muhammad Al Khabbaz. Abdul Rahman Al Sayigh is very well-known for copying the largest-size Qur’an in Muhaqqaq script.

The Safawi dynasty (1502-1736) in Iran also produced alluring and attractive masterpieces of Islamic art. During the reigns of Shah Isma’il and his successor (1524-1576), the Ta’leeq script was formulated and developed into a widely used native script which led to the invention of a lighter and more elegant version called Nasta’leeq (compound word from of Naskh and Ta’leeq). These two relatively young scripts soon were elevated to the status of major scripts. Although Nasta’leeq was a beautiful and appealing script, Turkish calligraphers continued to use Ta’leeq as a monumental script for important occasions.

The Persian calligrapher Mir Ali Sultan al-Tabrizi invented this script and devised the rules to govern it. Ta’leeq and Nasta’leeq scripts were used extensively for copying Persian anthologies, epics, miniatures, and other literary works but not for the Holy Qur’an. There is only one copy of the Holy Qur’an written in Nasta’leeq. It was done by a Persian master calligrapher, Shah Muhammad ِِAl Nishaburi, in 1539.

The reign of Shah Abbas (1588-1629) was the golden era for this script and for many master calligraphers, including Kamaludeen Hirati, Ghiyathul Deen Al Isfahani, and Imadul Deen Al Hussaini who was the last and greatest of this generation.

The Mughals lived and reigned in India from 1526 to 1858. This dynasty was the greatest, richest, and most lasting Muslim dynasty to rule India. The dynasty produced some of the finest and most elegant arts and architecture in the history of Muslim dynasties.

A minor script appeared in India called Behari but was not very popular. Nasta’leeq, Naskh, and Thuluth were adopted by the Muslim calligraphers during this era. The intense development of calligraphy in India led to the creation of new versions of Naskh and Thuluth. These Mughal scripts are bolder, the letters are widely spaced, and the curves are more rounded.

During the Mughal reign of Shah Jahan (1628-1658), calligraphy reached new heights of excellence, especially when the Taj Mahal was built. One name remains closely associated with the Taj Mahal, in particular with the superb calligraphic inscriptions displayed in the geometric friezes on the white marble. That is the name of the ingenious calligrapher Amanat Khan, whose real name was Abdul Haq.

Abdul Haq came to India from Shiraz in 1609 and Shah Jahan conferred the title of Amanat Khan upon as a reward. Amanat Khan was entrusted with the entire calligraphic decoration of the Taj Mahal. During Jahangir’s reign, he was responsible for the calligraphic work of the Akbar mausoleum at Sikandra and the Madrasah Shahi Mosque at Agra.

Muslims in China who used the Arabic scripts adopted the calligraphic styles popular in Afghanistan with slight modifications. Muslim Chinese calligraphers invented a unique script called Sini (Chinese in Arabic). The features of this script are extremely rounded letters and very fine lines.

Under patronage of the Ottoman dynasty (1444-1923), a new and glorious chapter of Islamic arts and architecture was opened, especially Arabic calligraphy. The Ottomans adopted the most popular calligraphic scripts of the time, but also invented few new and purely indigenous styles such as Tughra.

The most accomplished Ottoman calligrapher of all times was Shaykh Hamidullah Al Amsani who taught calligraphy to the Sultan Bayazid II (1481-1520). Uthman Ibn Ali, better known as Hafiz Uthman (1698), was another figure in a line of famous calligraphers. The most celebrated Ottoman derivative scripts were Shikasteh, Deewani, and Jali.